Social Media Geopolitics: The ‘Unofficial Geopolitics’ of Chinese Vloggers in Pakistan

Davide Giacomo Zoppolato & Karen Culcasi

Geopolitics

Davide Giacomo Zoppolato & Karen Culcasi. (2025). Social Media Geopolitics: The ‘Unofficial Geopolitics’ of Chinese Vloggers in Pakistan. Geopolitics. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2025.2499133

🚀 Access & Share

Get full access to this publication or share it with your network

Full Article

Official DOI AccessShare Research

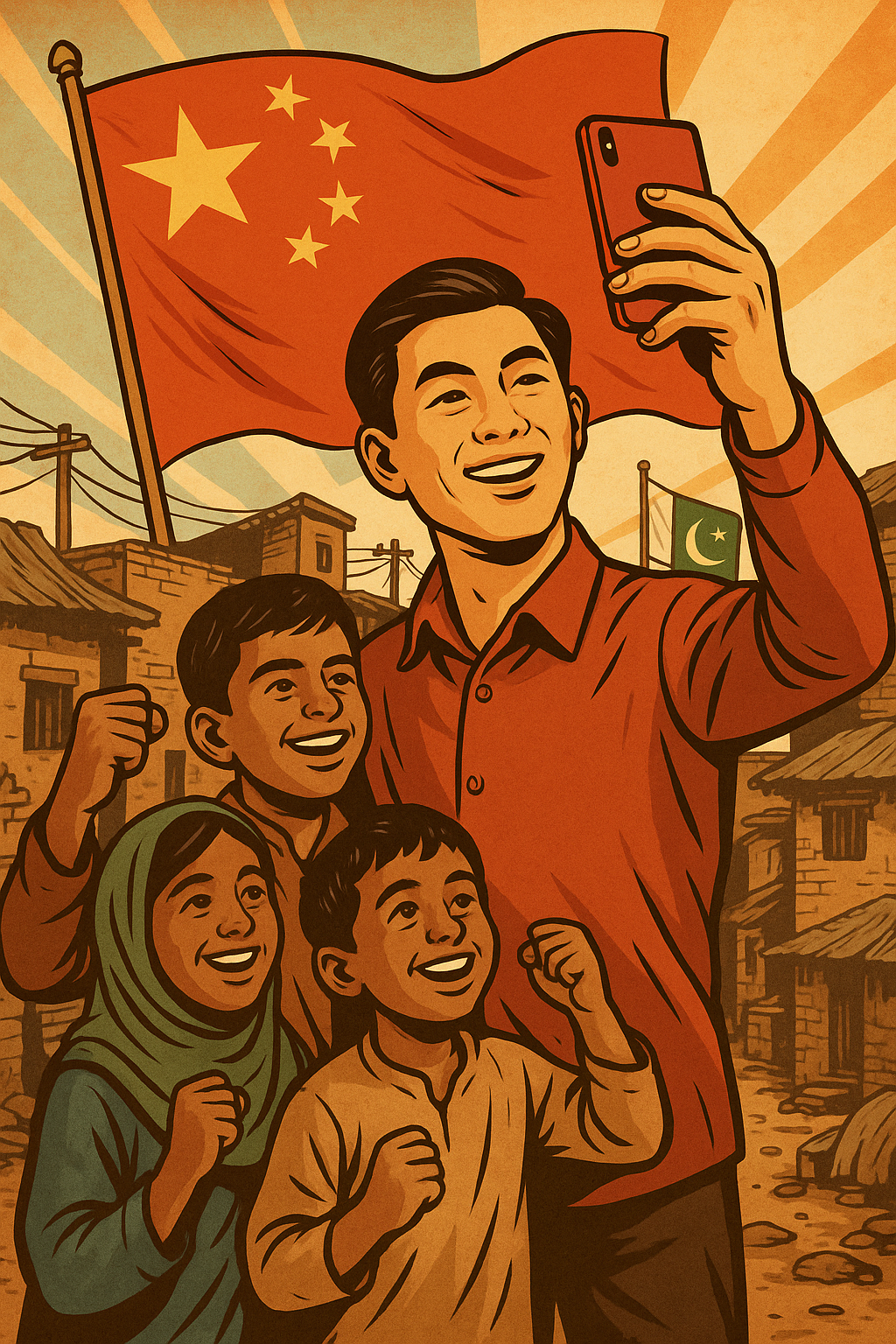

Social & ProfessionalOn September 21, 2021, a Chinese man in his early 30s who was residing inPakistan for work posted a video on Douyin - a China-exclusive video-sharing app owned by the same company behind the international socialmedia app TikTok - of his interactions with a Pakistani family. In thisnearly 10 minute-long video, he befriends a Pakistani man and then pro-ceeds to showcase the extreme poverty and uncleanliness of his newfriend’s home and family. Recognizing the challenges this Pakistani familyfaces, the vlogger decides to buy them groceries. This rudimentary videowas extremely popular on Douyin. As of May 2023, it had 267,000 likes26,000 comments, and was reshared 15,000 times. His post was far from unique though. Indeed, Chinese nationals in Pakistan have produced thou-sands of videos of their seemingly random interactions with Pakistanilocals. In most of these videos, the Chinese vloggers are friendly andmaintain a positive attitude towards helping the poor and strugglingPakistanis, but they are concomitantly degrading and paternalistic towardsthe Pakistanis they meet. In doing so, the vloggers recycle official Chinesegeopolitical discourses about China’s ability to develop Pakistan andimprove the lives of Pakistanis, but they do so in their own personalisedway that is patently unofficial.In this paper, we examine Douyin videos posted by Chinese nationals whoare residing temporarily in Pakistan as a case study of one way that geopoliticalproduction occurs within social media. Social media research is growingwithin critical geopolitics, yet it is still a burgeoning area with incredibleopportunities to develop new theories, concepts, and methods to analyse themassive array of geopolitics being produced and disseminated online.Considering social media’s extensive reach and impact, that its many plat-forms are replete with geopolitical discourses and practices, and that billions ofpeople across the globe now actively engage with geopolitics on social media,there is a need to more fully engage in social media as a newish site ofgeopolitical production. In the remainder of this paper, we first expandupon our point that social media is a site of geopolitical knowledge produc-tion, which we simply refer to as ‘social media geopolitics’. In that section, wehighlight how social media has shifted traditional power relations and blurredthe once seemingly clear elite/non-elite binary of geopolitical actors. We alsodiscuss the difficulty in applying the common divisions of sites of geopoliticalknowledge production that have dominated critical geopolitics for decades –those being the formal, practical, popular, and everyday – to social mediageopolitics. Next, we briefly elaborate on the concept of ‘unofficial geopolitics’.Then we transition to review some existing research methods for social mediageopolitics; and explain our data collection and analysis methods, which, wehope, might be useful tools for other scholars to examine social media. Wethen provide essential context of the geopolitical relationship between Chinaand Pakistan, highlighting the Chinese Pakistan Economic Cooperation(CPEC), which is a massive development project in Pakistan that is financedby China as part of the controversial Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In thissame section, we summarise the three official Chinese geopolitical discourses –‘Long Live the Chinese Pakistani Friendship‘, ‘Positive Energy’, and ‘NationalRejuvenation’ - that frame the geopolitical relations of China towards Pakistanand are recycled by the Chinese vloggers in ways that are paternalistic,degrading, and imperialist. Next, we provide a detailed examination of tenDouyin videos posted by Chinese nationals in Pakistan, highlighting how thesethree official Chinese discourses are recreated ‘unofficially’ through theircurated posts of their interactions with Pakistani locals. We conclude that there is incredible potential for critical geopolitics to engage more deeply andexpansively with social media as a site of geopolitical production.

Keywords:

It is well-known that social media has a massive reach and impact. Indeed, 63.9% of the global population uses social media, with users spending an average of 2 hours and 30 minutes per day on these platforms (Meltwater and We Are Social 2025). Each day, 95 million photos are posted on Instagram, 500 million tweets are tweeted, and 1 billion videos are watched on TikTok (Kemp 2022). Both the time spent on social media and the amount of content produced daily are staggeringly increasing, especially among young generations who rely on them as their main means of communication, entertainment, and for news and information (Weeks, Ardèvol-Abreu, and Gil de Zúñiga 2017; Westerman, Spence, and Van Der Heide 2014; Medina Serrano, Papakyriakopoulos, and Hegelich 2020). Geopolitical issues, content, and discourses are everywhere in social media, sometimes quite blatantly through propaganda or resistance movements and other times more subtly through banal statements, acts, or imagery.

We believe that it is crucial for critical geopolitics to more readily include analyses of social media in our work not only because of social media’s immense reach and for it being replete with geopolitics, but also because social media has shifted the traditional power relations of the production of geopolitical knowledge from being largely in the hands of the “elites” of statecraft, academia, and mass media to now including the “non-elite” or general populace. In other words, social media has blurred the once seemingly clear binary of elite/non-elite, and is evidenced in that countless people who are outside of traditional elite circles have gained fame, wealth, and launched careers as “influencers” on social media (Warren 2019). Some scholars have referred to this shift in power relations as creating a “new public sphere” that is (potentially) democratising and revolutionary (Kay, Zhao, and Sui 2015; Effing, Van Hillegersberg, and Huibers 2011; Druzin and Li 2015; Loader and Mercea 2012; Fuchs 2014). Within critical geopolitics specifically, several geographers have recognized the significance of social media in shifting power relations. Pinkerton and Benwell (2014) assert that social media has given people the “expression of geopolitical agency” (19). In Henry’s (2021) study of travel blogs as a form of geopolitics (817-18), he stresses that online blogging forces us to rethink how online media has shifted the control of geopolitical authorship, which are no longer just within the purview of the state and other elites. Similarly, Harris (2020), in his study of what he labels “Facebook geopolitics,” finds that “the line between writer and audience of geopolitical text has been blurred in the various social media formats, as individual users are invited to comment, like, share, and publish their own content”(4). And Dittmer and Bos (2019) recognize “how the creative practices of everyday people can produce—and circulate—geopolitical discourses and images through social media…,” and this has the “potential” to lead to “(geo)political action” (179). While there is often a celebratory tone in recognizing the blurring of traditional power relations and the increased agency of the general populace, it is crucial to recognize that the elites of statecraft, academia, and mass media, as well as Global North and neo-imperial powers, continue to exert incredible influence within social media (Aouragh and Chakravartty 2016). Thus, there are great opportunities to engage in new research and discussions about the shifting power relations that are occurring with social media broadly, as well as more focused work into how the general populace produces geopolitics in relation to the more traditional elite.

Research on social media from within critical geopolitics has been evolving for more than a decade now. Much of which has drawn upon a combination of “popular” and “everyday” geopolitics for its frameworks, concepts, methods, and analyses (Pinkerton and Benwell 2014; Dittmer and Bos 2019; Pickering 2017, 90; Suslov 2014; Castillo 2021). Again, “popular” and “everyday” geopolitics are two of the four common sites of geopolitical knowledge production (the other being “formal” and “practical”) that have been central to critical geopolitical studies over the past two decades.

“Popular geopolitics” typically focuses on the ways that geopolitical discourses are enmeshed in popular culture through studies of texts, symbols, and images. Traditionally, it has examined the ways that state or other dominant geopolitical discourses are varyingly recycled, altered, or challenged within professionally produced, “elite” mass media, like newspapers and magazines, movies, and comic books (Sharp 1993; McFarlane and Hay 2003; Falah, Flint, and Mamadouh 2006; Culcasi 2016; Dittmer 2005; Rech 2014; Kumar and Raghuvanshi 2022). Applied to social media, popular geopolitical analyses have shown how dominant discourses stemming from state powers are circulated, contested, and experienced on social media. For example, Suslov (2014) showed that Russian state powers tried to garner support for its invasion of Crimea, and examined the complex public debates that ensued online. Similarly, Zhang (2022) examined how the Chinese state media and private accounts used social media during COVID to bolster Chinese national identity and a sense of its superiority over Western, liberal regimes.

“Everyday geopolitics” incorporates concepts and research methods stemming from feminist geopolitics, cultural studies, and non-representational theory to examine how macro-scaled geopolitics intersects with people’s everyday life, experiences, perceptions, practices, and emotions (Dittmer and Dodds 2008; Painter and Jeffrey 2009; Smith 2020; Eraliev and Urinboyev 2024; Dittmer and Bos 2019; Highfield 2017; Duncombe 2019; Megoran 2006; Culcasi 2016; Öcal 2022). Everyday geopolitics typically focuses on people and communities that are not part of the “elite” circles of academia, statecraft, or mass media; and employs ethnographic methods like interviews that allow for depth in understanding people’s experiences. With its focus on “everyday people,” a term that greatly overlaps with what we refer to as the “general populace,” an everyday geopolitical approach to social media geopolitics creates incredible opportunities to study the ways that billions of people across the globe engage with geopolitical issues and discourses. For example, Warren (2019) applied an everyday geopolitics lens to render original insights into how macro-level geopolitical discourses on Islam and gender are being contested by Muslim women in Britain through their use of online platforms; and Williams et al (2022) show how Hindu nationalist politics are entangled in the daily lives and initiate spaces of the home through different platforms of digital life.

As fruitful as popular and everyday geopolitical approaches are (as well as formal and practical) for examining social media, they do not necessarily provide the framework needed to examine the new ways that geopolitics are being created, disseminated, and contested within the extensive web of social media. Indeed, we struggle to define our research on the geopolitics of Chinese vloggers’ posts of their interactions with Pakistanis within any combination of popular and everyday approaches. More specifically, we examine the production of geopolitical discourses from people who are part of the general populace, but their posts do not exemplify the everydayness of their lives. Instead, their posts are curated and edited from staged interactions so that they are interesting and can garner audience attention and popularity. Because their posts are highly curated and stylized, we find it challenging to make any credible assumptions about their everyday experiences or emotions. With our focus on vloggers’ posts, we are greatly examining texts, symbols, and images as discursive representations, and therefore our work seems akin to popular geopolitics. However, our project does not fit well within popular geopolitical framings either because we are examining the texts and images of people outside of the circles who have traditionally controlled popular culture and geopolitics. The formal, practical, popular, and everyday divisions of critical geopolitics are helpful pedagogical tools and entry points for understanding the sites of geopolitical production, but they can also be so interconnected that it can be challenging to prioritise one approach over another. We believe that social media exemplifies, if not fuels, such overlaps, as it is a site where media elite, state and academic actors, and of the general populace all help to create. Applying one of these divisions might be entirely suitable for some focused studies on social media, but we find that the popular and everyday (formal and practical too) are so entangled that we frame social media geopolitics as its own, newish site of geopolitical production.

Keywords:

To the burgeoning field of social media geopolitics, our case study contributes to examinations on the ways that the general populace, perhaps as influencers, participate in the production and dissemination of geopolitical discourses through an analysis of the texts, images, and symbols in social media posts. We examine the posts by Chinese vloggers in Pakistan of their typically friendly and casual interactions with Pakistani locals. The posts seem to be primarily for entertainment, to draw viewers’ attention, and perhaps to gain fame or profit, but the posts are also replete with their own reworkings of official state discourses of the Chinese Communist Party. Pinkerton and Benwell (2014) use the terms “unofficial diplomacy” and “citizen statecraft” to refer to the ways that social media posts “imitate and/or mimic” official diplomatic discourses and practices in their study of the Falkland Islands (14). In engaging with state discourses, social media users normalize and popularize official geopolitics making state narratives ubiquitous and accessible to an audience of million. We use the term “unofficial geopolitics” to refer to a type of geopolitical production in which the general populace - outside statecraft or elite - recycle official state geopolitical discourses through their personal style and content. In our case, Chinese vloggers are not parroting state discourses, but add paternalistic, degrading, and imperialist sentiments to the established state discourses.

We opted to focus on Douyin due to its extensive reach, with over 743 million monthly users; and because of its high user engagement, averaging more than two hours per day with Chinese users (ByteDance 2023). This makes Douyin the most used video-sharing social media in China. Douyin is owned by ByteDance, a Beijing-based internet company who specialises in Artificial Intelligence and machine learning. Launched in 2016, Douyin is an enclosed digital space for Chinese nationals and foreign residents in China. One year after Douyin was released, and following ByteDance’s acquisition of the U.S. app Musical.ly, the hugely popular (and critiqued) international version named TikTok was released. In examining social media geopolitics, we found two broad methodological approaches in the literature. The first is a quantitative-oriented approach that employs text mining and other automated content analysis techniques to extract insights, geospatial information, and patterns from large sets of social media data. For example, Moreno-Mercado and Calatrava-García (2023) used text mining techniques to examine the geopolitics of the Israeli Defence Forces on Twitter. Similarly, Sufi (Sufi 2023) employs quantitative content analysis to examine the Russia–Ukraine conflict on Twitter. The second approach draws on qualitative research methods, adopts a more critical angle, and commonly espouses discourse analysis (Kinsley 2013). For example, Henry (2021) uses a “static-word netnography” to examine the texts of travel bloggers in forming geopolitics (818). Similarly, Pinkerton and Benwell (2014) employ discourse analysis on advertisements posted online and the discussions they generate about Falkland Island geopolitics. Other researchers have combined the analysis of text with visual images produced on social media such as maps, flags, and cartoons (Suslov 2014; Harris 2020; Castillo 2021). And, as noted above, there are also in depth studies of everyday experiences with social media. In our research we employed qualitative methods of discourse analysis to examine spoken words, songs, images, text, symbols, and the actions and engagements of the people in the videos. While our methods required some experimentation, we eventually developed a four step process that allowed us to sample from a large amount of data on social media, to identify general trends in the posts, and then to examine geopolitical discourses in detail. As we explain next, these four steps are: geopolitical contextualization, preliminary research and familiarisation, data collection, and analysis. Contextualization We began our project by contextualising the China-Pakistan geopolitical relationship through an in-depth literature review of the historical development of their geopolitical relations. Contextualization was crucial in grounding our analysis of videos, so that we were familiar with key themes and discourses that have shaped China-Pakistan geopolitics. Preliminary Research/Familiarization Second, we familiarised ourselves with Douyin’s platform, including reviewing literature on this platform and conducting multiple viewing sessions to explore its functionality, features, interface, and video selection. Then we conducted numerous experimental searches and analyses of Douyin posts about the China-Pakistan geopolitical relationship. Data Collection Following the preliminary research, we conducted a more informed and narrower search on the China-Pakistan geopolitical relationship, which resulted in the data that is the basis of this paper. Social media platforms, including Douyin, allow users to search content of interest with keywords. Based on a platform’s functioning, search keywords return the most viewed and popular content, partly because social media curates video selection to that specific user through algorithm recommendations (Gillespie 2018). To reduce platform curation, we did not use personal account logins and ensured a neutral location to prevent algorithmic content suggestions and targeting based on metrics like user engagement and geolocation. We conducted our search using a VPN with the location set in Beijing and without logging in the app. After ensuring that our location and the login would not impact the data retrieval, we queried Douyin with the keyword phrase “life in Pakistan.” We chose this search term so that we would retrieve videos posted by Chinese nationals about their time in Pakistan. We found Douyin as other video-based platforms particularly useful for gathering videos posted by the general Chinese populace because its algorithm allows novice vloggers the same opportunity to be visible to viewers as established or celebrity vloggers (M. Zhang and Liu 2021). Our search, which we conducted in July 2023, yielded 216 Douyin videos. All 216 of these posts were reviewed multiple times by the first author, who is fluent in Chinese. We then narrowed our sample to exclude videos that were not uploaded by the original vlogger (meaning they were not reposts); and to exclude posts in which the vlogger did not specifically state they were residing in Pakistan. We also removed posts in which the vlogger made any mention or reference to them being a representative of the Chinese government. In cases where there were multiple videos from the same vlogger, we selected only one of that individual vlogger’s, so as to not overrepresent one particular person. In those instances, we chose the post with the highest number of likes. Lastly, we excluded video posts that included little to no content related to China-Pakistan relations, like daily beauty routines or posts about food and meals. From the 216 original returns, there were 10 videos that met these above criteria. Data Analysis Following our data collection, the first author transcribed and translated the ten posts into English, noting specificities and rhetorical uses found in the Chinese language. Once the transcripts were prepared, we jointly coded them. We coded the textual transcriptions, the video descriptions, added text and visuals, and hashtags. We then connected emerging themes and patterns across the videos and related them to the three geopolitical discourses we identified in our contextualization step as the most relevant in framing China-Pakistan geopolitical relations.

Keywords:

Pakistan and China established formal diplomatic relations in 1951, two years after the founding of the People’s Republic of China. In doing so, Pakistan became one of the first non-communist countries to recognize the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as the legitimate government of China. Then, in 1963, geopolitical relations between the two states focused on attempting to rectify the territorial dispute in the Kashmir region. Their cooperation then broadened to encompass scientific, cultural, military, and commercial matters (Small 2015; Boni 2019; Abb 2023; Karrar 2022). Pakistan also played a crucial role in facilitating US President Nixon’s visit to China in 1972 by acting as a mediator and diplomatic conduit between the US and China.

In April 2013, the China-Pakistan relationship grew immensely through their “similar development path” when premier Li Keqiang visited Pakistan and signed the Memorandum of Understanding on Cooperation for the Long-term Plan on China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Pakistan’s previous prime minister, Nawaz Sharif, said at the launch of CPEC in 2013 that the two countries’ relationship is “...higher than the Himalayas and deeper than the deepest sea in the world, and sweeter than honey” (The Telegraph 2013). Crucially for China, the CPEC is the ‘flagship project’ of their global BRI (Abb, Boni, and Karrar 2024). Then, in 2015, China formally granted Pakistan the special status of “all weather strategic cooperative partners” (Li and Ye 2019). Pakistan is the only state in the world to have this status with China. More recently, in 2024, Wang Yi, China’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, underscored how the partnership with Pakistan is built around mutual support on core interests, advancing practical cooperation and development, ensuring common security, and upholding international fairness and justice (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People's Republic of China 2024).

Buttressing the CPEC economic and investment partnership, the CCP has also created and promoted overlapping geopolitical and nationalist discourses that frame their geopolitical relationship with Pakistan and are recycled in the Douyin post. These include “Long Live the Chinese Pakistani friendship,” “Positive Energy” and “National Rejuvenation” (Zeng 2020; Hartig 2018; Garlick and Qin 2023).

Xi Jinping, the president of the People’s Republic of China since 2013, has frequently used the phrase “Long live China Pakistan Friendship” (Xi 2015). On Douyin, Chinese politicians, media outlets, and citizens regularly use this phrase to highlight the strong, bilateral partnership between the two countries and peoples. Within this discourse of “friendship,” the term BaTie, which means “iron brothers,” is commonly used to indicate the strength of the friendship between the two states and its people.

Maintaining and spreading “Positive Energy” is a second official Chinese discourse that the CCP has promoted and that is evident in Douyin. Positive energy, a discourse launched in 2012, refers to Chinese citizens maintaining positive behaviours, emotions, and attitudes (Yang and Tang 2018; Z. Chen and Wang 2019). The essence of Positive Energy is that Chinese people should speak and think positively, and actively work towards the betterment of self, community, and global society. It is a feeling and attitude that can be propelled within oneself and onto other people. Being positive, or having “Positive Energy,” is poised as being good for both the individual and society (Chen and Wang 2019). Embracing positive energy means recognizing that there are challenges and difficulties in life but that these can be overcome.

In the same year that “positive energy” became an official CCP discourse, so too did the party begin to stress the importance of China’s “National Rejuvenation.” The central goal of National Rejuvenation is to revive the Chinese state and its people to the glorious status it once had (Garrick and Bennett 2018; Suryadinata 2017). According to Chinese historiography, China was a powerful world leader for at least 5,000 years. Yet, due to British imperialist policies and practices in China in the 1870s, as well as occupations of Chinese territory by Japan in 1800 and 1931, China experienced significant decline. The goal of National Rejuvenation is to remedy this decline and restore China’s status as a leading global power. National Rejuvenation applies to all people and ethnic groups within China’s diverse society, including Chinese people living outside China’s borders (see: Dikötter 2015; Ge and Hill 2018; Hui 2011). Xi Jinping, in a 2012 speech, stated that “National Rejuvenation” is the “greatest dream of the modern Chinese Nation.” He continued: “This dream embodies the long-cherished wish of several generations of Chinese people, reflects the overall interests of the Chinese nation and the Chinese people, and is the common expectation of every son and daughter of the Chinese people”(Xi 2012).

These three official CCP discourses - “Long Live the Chinese Pakistani Friendship,” “Positive Energy,” and “National Rejuvenation” - are clearly present in the Douyin videos we examine in the next section. While these discourses were developed and promoted by the CCP, Chinese vloggers actively draw upon and normalize them through their own unique styles, thus engaging with what we consider to be “unofficial geopolitics”.

Keywords:

The 10 videos we examine below, like most videos on Douyin, are edited prior to posting but are still of amateur quality. Nevertheless, their videos are impactful; with likes per video reaching 1.582 million, 75,000 comments, and 17,000 reposts. The 10 videos range in length from 1 minute and 37 seconds to 9 minutes and 54 seconds. The vloggers include 9 different men and 1 woman. All the encounters in the posts between the Chinese vloggers and local Pakistanis are orchestrated to some degree, even though the vlogger often tries to make them appear as unscripted and accidental. All the interactions are mediated by Pakistani guides who speak Chinese, English, and Urdu. The camera is either in the hands of the vlogger or the local guide, and never the Pakistani local. In other words, the Chinese vloggers are the protagonists and producers of the videos and the Pakistani locals are their objects of interest. Friendship The staging of friendship between the Chinese vloggers and Pakistani citizens is a central theme in all 10 videos. Pakistanis are typically friendly and welcoming towards the vloggers - whether on the street, in a market, or in their home. The Chinese vloggers typically express keen interest in the lives of the Pakistanis they meet. Often, the vloggers use the phrase “Long Live China-Pakistan Friendship” as well as the term “iron brother” during their interactions with Pakistanis. The vloggers commonly speak to the camera to reflect on the friendly relationships they have with the Pakistanis they’ve met; which often includes telling the viewer that these personal friendships are akin to the strong relationship between China and Pakistan. The friendships that are spotlighted in the posts are, however, uneven and paternalistic. The vloggers are the subjects of the posts who narrate their experiences, while the Pakistanis are the objects of vloggers’ gaze and are typically positioned as dirty, impoverished, and needing the help of the Chinese vlogger. Indeed, the vloggers often demonstrate their friendliness towards their new Pakistani friends through acts of largess, for example, by buying them groceries, a meal, shoes, or a haircut.

In the video that we noted in the introduction, a 30-year-old Chinese vlogger begins his post by showcasing several wealthy Pakistani homes in a neighborhood in Islamabad that he is visiting. The camera then pans to the street where a middle-aged Pakistani man, who is wearing a grey salwar kameez (a traditional Pakistani dress), is walking towards him. The Pakistani stranger is extending a gesture of kindness and friendship by offering the Chinese vlogger an orange. The vlogger tells his audience that “I was given an orange just because he saw that I am Chinese.” The vlogger continues that “He’s so friendly to Chinese people … and I must live up to this friendship.” The vlogger, after asking for the name of the Pakistani man, and then failing to pronounce his name in Urdu, decides to refer to him using the term Tie Zhu, which is similar in meaning to that of “iron brother.” The vlogger then asks the man he calls Tie Zhu if he can visit his home. The two new friends walk together to the Pakistani man’s home (which seems rather staged but is portrayed as unplanned). The vlogger is surprised to discover that Tie Zhu and his family live in a tent, which stands in stark contrast to the wealthy homes he was just showcasing. The Pakistani’s home and lifestyle is now on stage, including his poor, dirty, and innocent looking children. The vlogger expresses concern for the well-being of Tie Zhu’s family, especially the children. Motivated to help this poor Pakistani family, the vlogger decides to purchase groceries for the family. The camera then follows the vlogger to a local store where he purchases several bags of food. One item the vlogger buys for his new friend is a large bag of oranges (Figure 4). In addition to providing some sustenance to the family, the bag of oranges is symbolic in that the vlogger is giving back exponentially what he was given by the Pakistani man earlier while on the street. The vlogger returns to their home to present the family with these groceries. Then, at the end of the video, the vlogger emphasises the significance of the China-Pakistan friendship and tells his Douyin followers to support his endeavour to help Tie Zhu and his family. Lastly, the vlogger say the phrase “Long Live the China Pakistan friendship” in Chinese and Tie Zhu repeats it in Urdu.

Figure 4 – Vlogger gifting groceries, including a large bag of oranges, to a Pakistani family he just befriended. In another video, a Chinese man in his early 30s is driving around Lahore when he suddenly notices a symbol of the China-Pakistan friendship painted on a concrete wall under a bridge. The symbol is of a Chinese and a Pakistani flag adjacent to one another. To the vlogger’s disappointment, the flag-painting is visibly dirty. He stops and explains to the camera that the Chinese flag represents his country and he is disappointed to find it dirty, with what looks like copious amounts of bird faeces. Determined to clean the entire symbol, but most importantly and firstly the Chinese flag, the vlogger finds a ladder, a sponge, and some water. Seemingly unexpectedly, three young Pakistani men in their early and mid-twenties - dressed in work-clothes - approach him, inquiring about his nationality and what he is doing. At first, the vlogger doesn’t pay much attention to them, and they leave; but they soon return with their own sponges, brushes, and buckets of soapy water. They offer to help the vlogger clean this symbol of the Chinese and Pakistani relationship. The vlogger happily agrees to work with these men and as the day progresses, evidenced by the change from daylight to night, the group of new friends have completed their work and made the flags anew. The vlogger is delighted with the Pakistanis’ help, their friendliness towards him, and for respecting China’s national flag. He invites them to lunch at a nearby McDonald's, an offer they accept, and then the group eats together with the vlogger paying the bill. The video concludes with three of vlogger’s new Pakistani friends standing in a row and the vlogger awkwardly giving each one of the workers a hug. The vlogger then reflects on his experience with these Pakistani men and states that, “I came to understand even more what iron brothers mean and what China-Pakistan friendship is [...].” The vlogger then wishes for the enduring friendship between China and Pakistan and concludes the video by saying, “Bless you, my Batie friends! May our friendship last forever.” Positive energy Positive Energy is another major theme in the Chinese vloggers’ videos. Again, Positive Energy encourages Chinese nationals to actively contribute to the betterment of oneself and the world by maintaining a positive, uplifting attitude and engaging in action that can help propel positivity (C. Zhang 2022). Vloggers on Douyin have drawn on the idea and enactment of Positive Energy to such a large degree that Douyin features a trending section that promotes videos focusing on spreading Positive Energy (X. Chen, Valdovinos Kaye, and Zeng 2021). The term “positive energy” is explicitly stated in four out of ten videos in our sample, but it is enacted in all ten of them. Specifically, vloggers use the positive energy discourse when they assert that the challenging situations of Pakistani life can be improved. Vloggers often encourage their viewers to show compassion for the hardships faced by poor Pakistanis. Some vloggers highlight that education and employment will lead to a better future, some stress finding joy in simple things in life, and others express admiration for the strong work ethic of Pakistanis that may lead to their betterment. The vloggers often comment that their own goodwill toward Pakistanis can propel positive energy. Several of the vloggers end their posts by highlighting that there is much joy and warmth in the world, which is something that they just demonstrated through their videos.

For example, a Chinese man in his late thirties posted a video in which he begins by recognizing the close, friendly connections between China and Pakistan. He zooms in on a Chinese flag that is flying close to a Pakistani flag to illustrate his point. He then pans to a village and refers to the villagers as BaTie (iron brothers). The majority of his post, however, emphasises the workings of positive energy. He explains that when he wakes up in the morning, the children in this village are already up, working hard on their chores and getting ready for school. He is particularly impressed by this because, as he explains, the weather is very hot and because the villagers do not have modern conveniences that would make their lives easier. A bit later in the video, he films a villager with a broken axe. He explains that it broke because the villagers work so hard. The broken axe symbolises the resilience and strength of the villagers in the face of adversity. The vlogger also highlights the simplicity and beauty of life in the village. He records part of a sunset, pointing out the evening glow on both the east and west sides of the village, which he refers to as a blessing. He concludes by sharing a clip of his Pakistani friends dancing, and notes that they have the courage and determination to overcome difficulties in life. The vlogger encourages his audience to keep working hard and to work together to change the future. He ends by saying: “every day we are working hard to change… brave villagers are not afraid of difficulties… Come on, change and fight again tomorrow.” He ends by giving a thumbs-up to nearby Chinese and Pakistani flags flying in a ramshackled landscape. The text on the screen says “don’t be afraid of difficulties” (Figure 5).

Figure 5, ‘Don’t be afraid of difficulties’

In another video, a young male vlogger is sitting at an outdoor restaurant, enjoying his food. He notices an old Pakistani man who is collecting trash nearby. The Pakistani man, who is wearing tattered clothes and dirty shoes, walks toward the food counter, stares at a burger being cooked, and then asks a man at the counter for a free burger. The owner of the burger stand refuses to give the old man a burger. The Chinese vlogger is upset by the owner’s reactions to the poor man. He gets up to intervene and explains to the owner that the old man will be his guest. Then, the vlogger orders a burger for the man and pays for it. The old man and the vlogger sit together and the older man begins eating quickly. The vlogger encourages him to slow down and enjoy the meal, but then realises that he is starving. As he eats, the old man says, “Chinese good people, Chinese good good people.” After the meal, the Chinese vlogger offers to give the old man a ride home, but the Pakistani man is worried that he will dirty the car. Yet, the vlogger insists on giving him a ride and reassures the man that he is not worried about the car. After dropping the man off at his home, which is in dire condition, the vlogger reflects on the challenges that people experience globally and stresses that with positive actions, like the one he just demonstrated, that individuals and society can be improved. He tells the camera that “all people face difficulties at times. And this old man's situation resonates with me. I hope to contribute my own efforts to ensure that those who are struggling are treated equally.”

National Rejuvenation In tandem with friendship and positive energy, the video posts in our sample recirculate the idea that China and Chinese people are strong, powerful, and prosperous, which stems directly from the Chinese National Rejuvenation discourse. Several vloggers focus on their love of the Chinese nation, of being patriotic, and of defending their “motherland.” In the video discussed above in the section on “friendship,” in which the vlogger is helped by Pakistanis in cleaning the painted image of the Chinese and Pakistani flags, the vlogger is motivated by his national pride and desire to clean the Chinese flag. While friendship is a powerful theme in that post, so too is National Rejuvenation. Indeed, at the end of the video he reflects and tells his audience that “I believe that every compatriot living in a foreign country would neither want nor allow any dirty things on our national flag.”

There is another video in which the vlogger focuses on the Chinese flag. In this video, the Chinese vlogger notices that someone is using his country’s flag as protective covering for a parked motorcycle. He expresses his discomfort about this to the camera, stating that he does not want his national flag to be used in this inappropriate manner. The man then asks the camera whether the motorcycle owner respects China. He looks around for the owner of the motorcycle and inquires about it at a nearby shop. The vlogger engages in a heated conversation with a Pakistani man in the shop, explaining that the cover on the motorcycle is a Chinese flag and that using it in that manner is disrespectful to China. Unable to find the owner of the motorcycle, he decides to remove the flag, but out of respect to the motorcycle owner, he purchases a new cover at a nearby shop. At this shop, there are several covers for him to choose from, but in a gesture of his wealth, he buys the most expensive one. He then returns to the motorcycle, removes the Chinese flag, folds it with great care, and replaces it with the new cover he just bought (Figure 6). The motorcycle owner is still not present, but four Pakistanis dressed in salwar kameez watch him as he performs this act. The onlookers then approach him and reach out to touch the flag. The Chinese vlogger refuses their attempt to touch the Chinese flag, yet accepts their help in covering the motorcycle with the new cover.

Figure 6, Folding the Chinese flag As the vlogger folds the flag, a popular Chinese nationalist song plays, which includes the lyrics: “Five-star red flag, you are my pride. Five-star red flag, I am proud of you. Cheering for you, I bless you. Your name is more important than my life.” Then, the vlogger hands some money to a Pakistani man dressed in a clean salwar kameez. Although the Chinese vlogger in this video is less friendly than others, he still ends on a positive note, emphasizing the friendship between Pakistan and China. In fact, he concludes the video by saying “May China Pakistan friendship live forever.”

Keywords:

Through our case study of Douyin, we have demonstrated one particular way that Chinese nationals in Pakistan are producing “social media geopolitics”. In their posts of seemingly random interactions with Pakistani locals, they are engaging in what we term “unofficial geopolitics,” as they recycle the official CCP’s discourses of “Long Live the China-Pakistan Friendship,” “Positive Energy,” and “National Rejuvenation.” While each vlogger does so in their own stylized ways, all the posts echo these discourses by focusing on Chinese goodwill and friendship, of understanding the hardships faced by Pakistanis and maintaining positive energy, and of China and the Chinese people being a strong, powerful, prosperous nation with the ability to help poor Pakistanis to improve their lives. While the vloggers seem altruistic in their actions, their friendships are uneven and paternalistic in ways that echo European imperialist approach to colonial subjects who they portrayed as needing to be saved - fed and cleaned - by imperialist who have more power and knowledge (Fanon 2002; Memmi 2003, Castillo 2021). Indeed, even as the video posts centralise friendship and positive energy, the Chinese vlogger is positioned as being able to help, as being more advanced, and as knowing how to solve the Pakistanis’ problems of hunger and uncleanliness. As such, the vloggers are drawing on and normalizing official Chinese discourses that frame the CPEC and that position China as a friendly but superior ally that can develop Pakistan and help improve the lives of Pakistanis. Through their own personalized content, they recycle a version of the uneven geopolitical relationship between China and Pakistan but the vloggers’ posts are rife with paternalistic, imperialist, and degrading actions. Our findings, however, do not represent a definitive relationship between the Chinese general populace and the CCP. Other studies of Chinese social media geopolitics have found diversity, debate, and contention between the general populace and the CCP (Kay, Zhao, and Sui 2015; Woon 2011; C. Zhang 2022). That there are varied findings on the relationship between Chinese nationals and the CCP demonstrates that “social media geopolitics” is complex, evolving, and merits more research.

Social media are ubiquitous and powerful platforms for the production and dissemination of geopolitical discourses and engagements. TikTok, Telegram, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitch, YouTube, WeChat, Reddit, and Kuaishou – most notably - are increasingly becoming people's primary source of news and information. Crucially, social media has shifted traditional power relations, as a person now needs little more than a phone and an internet connection to engage in geopolitical production. As such, there are great opportunities for critical geopolitics to develop concepts and tools to examine this newish form and site of geopolitical production and provide original insights into shifting geopolitical power relations.

📬 Stay Updated

Subscribe to receive the latest publications, insights, and updates.